On March 14, the Cabinet of Ministers approved an unusual order No. 103-r: the Kyrgyz Republic will enter into an agreement with Russia to purchase 64,000 shares of the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB) for $64 million.

The Eurasian Development Bank is a major regional financial institution with a project budget worth billions of dollars. The main participants, who are also the primary recipients of funding, are Russia and Kazakhstan. The Kyrgyz Republic joined the bank nominally after its establishment and holds a mere 0.1% share of the capital. After acquiring a portion of Russia’s stake in the bank, our share in the EDB will increase to 4.3%.

The first question that arises is – does our budget have an excess of funds, leading us to acquire minority stakes in regional development banks? Is there no better way to allocate the $64 million? We delved into the matter, and it turns out that the situation is not as alarming as it may seem, although there are some nuances.

Oddities: numerous

The agreement approved by our government to purchase EDB shares from Russia is riddled with peculiarities.

Firstly, let’s consider the price. The EDB has been in operation since 2006, and every year it raises funds in the market (the bank has numerous bond issues), invests in a variety of projects, and generates operating profit. Here is the data from the 2022 report:

Any finance expert would argue that the market price of shares in such a bank cannot be at face value. They could be worth more – if we assume that all the bank’s investments are market-based and will eventually be returned to the bank while generating profit. Alternatively, they could be worth less – if we assume that the bank will need to write off part of its investments. However, the shares are certainly not worth exactly $1,000 per share, as set in 2006. Yet, for some reason, Kyrgyzstan is buying them at face value.

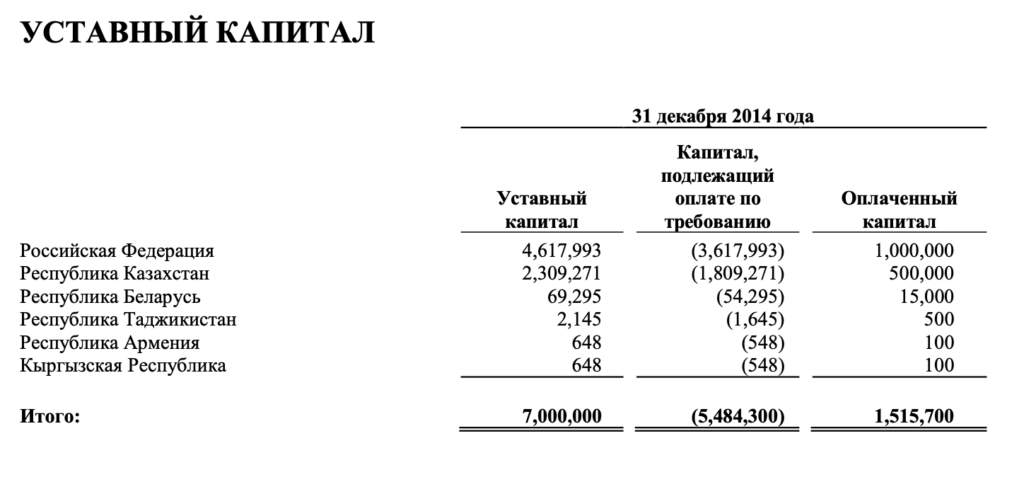

The second oddity arises from the bank’s capital structure and may be less apparent to readers. The bank’s authorized capital is not the amount that is currently paid by participants (just over one and a half billion dollars) – it stands at 7 billion. The difference between 1.5 and 7 billion is the so-called «capital payable on demand».

When considering that the Kyrgyz Republic should increase its stake in the bank, it would be more logical to not redistribute already paid shares, but rather to receive direct investments from us in the capital – especially since this is legally expected from all participants who have not paid their full share («capital on demand»). However, we are buying out part of Russia’s stake instead.

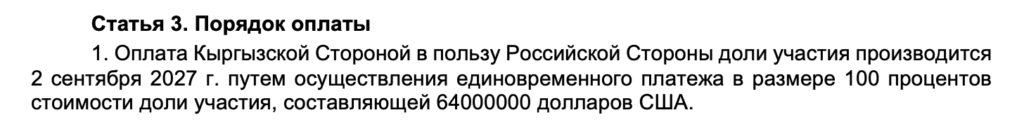

However, the most significant oddity lies in the payment terms for the shares. According to the agreement, the Kyrgyz Republic acquires the shares immediately, but is obligated to pay for them only on September 2, 2027 – more than 4 years from now!

Is this a typical commercial practice? Would you grant someone shares in your business virtually for free, along with the rights to receive dividends, participate in management, and so on, with payment due only after 4 years? Moreover, at the «old» face value?

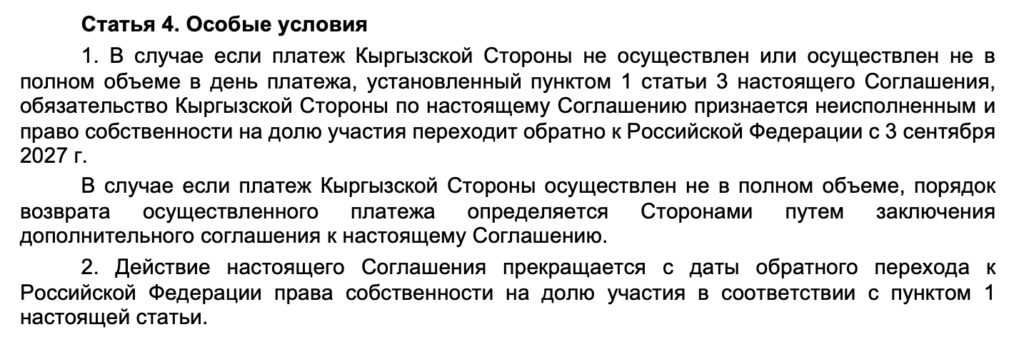

Additionally, the final peculiarity is the lack of explicitly defined consequences for non-payment.

It seems to be implied by the agreement (we will revisit the word «seems» later) that if we do not pay for the shares by September 2027, we would simply have to return them, and the agreement would be terminated.

In colloquial terms, this resembles more of a «trial period» than an actual sale.

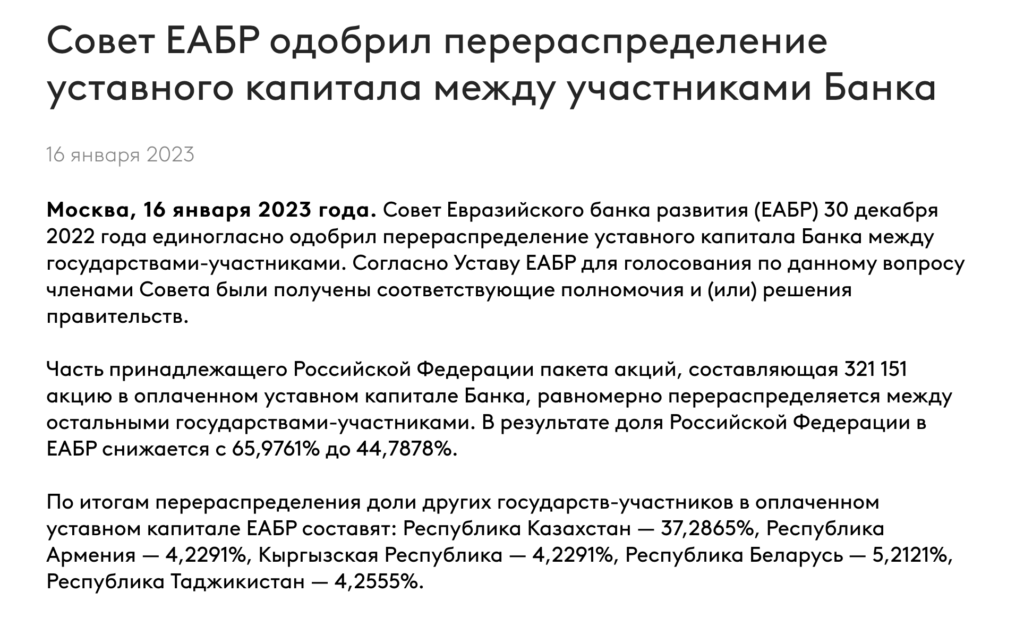

Other shareholders are also purchasing stakes, and it is equally strange.

As it turns out (all information is from public sources), other EDB member countries are simultaneously buying smaller stakes in the bank from Russia. Consequently, Russia’s stake, which previously provided controlling interest, is reduced to non-controlling.

Kazakhstan is also experiencing non-market conditions when purchasing Russian EDB shares: their acquisition will be paid for within 4 years, albeit with real money involved in the transaction.

However, the payment for shares might prove to be as illusory as in our country’s case. Here is what the Minister of Finance of Kazakhstan said about this:

It is evident that redistributing part of Russia’s stake among other bank shareholders is solely aimed at insulating the EDB from the risk of being subject to Western sanctions targeting Russian financial interests.

Russian oligarchs, who faced personal sanctions in 2022, actively employed this tactic (quickly selling all or part of their holdings to relatives, trusts, or partner employees «the day before» or immediately after being sanctioned), albeit with varying degrees of success.

We are not alone in drawing this conclusion: Russian Forbes and Russian Kommersant, citing their sources, report that Russia’s urgent relinquishment of a controlling stake in the bank is indeed an anti-sanctions maneuver.

Maybe it’s better to buy?

Despite the evidently scheming nature of the transaction, one might ask – if we have the opportunity to acquire a stake in this bank at face value, should we seize it?

Our conclusion: even a cursory analysis of the EDB’s financials suggests that it is better to hold these shares temporarily at the behest of our Russian counterparts and then return them in good faith.

EDB is not a bank in the conventional sense of the word. It is a «development bank» – essentially an interstate mechanism for redistributing state funds from participating countries and borrowed funds (a significant portion of which are also likely bought out by state-affiliated structures) for large projects within the bank’s member countries.

It is crucial not to conflate the bank’s current (operating) profitability, which it consistently demonstrates and is formed as the difference between interest earned on loans and interest paid on borrowings, with the reliability of its investments. A considerable portion of these investments are infrastructure projects whose profitability appears promising in business plans but may be uncertain in reality. These projects are primarily strategically important for the country initiating them (primarily Russia, which is developing its transport infrastructure using EDB funds), and their profit component often seems artificial (e.g., assuming that the road will be tolled).

Here are some examples of EDB’s investments in Russia:

• Construction of the Western High-Speed Diameter Highway (St. Petersburg) [$363 million]

• Construction of the Togliatti bypass road – part of the Europe-Western China transport corridor

• Construction of the Western High-Speed Diameter motorway near the port transport hub of St. Petersburg [10 billion rubles and 191.3 million euros]

• Construction of the Central Ring Road (TsKAD), a priority of Russia’s transport strategy that facilitates cross-border transportation within the international corridor «Europe — Western China» [12 billion rubles for the Central Ring Road-3, up to 14 billion for the Central Ring Road-4].

There are legitimate concerns about the profitability of these investments. Such investments do not hold strategic importance for Kyrgyzstan. Perhaps the EDB’s loan investments within Kyrgyzstan itself are more strategically valuable for us?

There are only three recipients of EDB credit lines in our country, and two of them are not strictly Kyrgyz recipients.

One is a subsidiary of the Kazakh Halyk Bank.

The other is the Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund, which has struggled to invest the funds promised to Atambayev by the Russian President (only $1 billion). It is essential to understand that investments from the RKDF are not granted without the approval of the Russian side.

The third recipient is our Aiyl Bank, which received a loan to finance small and medium-sized businesses. The issue with this loan is that it is provided in dollars, while Aiyl Bank lends to small and medium-sized businesses in soms (perhaps, except for purchasing foreign equipment in foreign currency). Consequently, if inflation rises, the recipient bank may face exchange rate risks.

Returning to the question of the EDB’s profitability risks, it is worth noting that some of its borrowers began facing sanctions last year. For instance, the State Transport Leasing Company.

|

|

In 2022, GTLK Group companies were subject to blocking sanctions from the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, which, among other things, made it impossible to pay coupon income to the holders of Eurobonds issued by GTLK Europe Capital DAC and GTLK Europe DAC.

Might the Kyrgyz budget suffer?

Can the financial scheme involving EDB shares backfire on our budget? Could a situation arise where, in the event of non-payment for the EDB shares received from Russia, Russia will not be satisfied with the return of the shares but will demand either full payment or penalty fees from our country?

At first glance, after reading the text of the Agreement, it seems that there is no risk. However, lawyers argue that there are several nuances to consider.

The agreement does not specify under which law it should be interpreted. There are only two options – either Russian law or Kyrgyz law. In both cases, civil law provides for compensation of losses in the event of non-fulfillment of obligations. The agreement itself does not directly exempt the Kyrgyz side from the norm on compensation for losses; it only states that if payment is not made on time, the shares will be returned to Russia, and the agreement will cease to be in force. However, this does not necessarily preclude claims for damages. It is informally understood that Kyrgyzstan is providing a service to Russia, not vice versa, but no one knows what will happen in 2027.

The second possible issue is if, due to increased sanctions or some other force majeure (although very predictable), the Kyrgyz Republic is physically unable to return the shares to Russia. Then, under any applicable law, there will be grounds to demand compensation for losses from the Kyrgyz side. On the other hand, the shareholder register is maintained in a territory currently friendly to Russia, so the risk is not that high.

Can the Kyrgyz budget benefit?

It is quite likely. The EDB continues to show operating profit, and there is a chance that dividends will be accrued on the block of shares under the Kyrgyz Republic’s ownership during the period of ownership. Informally, this will be a payment for shielding a bank so crucial to Russia from risks, but in reality, it would be money for our budget.

Considering all the facts, our conclusion is that the deal is favorable. Now, we should approach the Russian government with a proposal to buy out shares in several of Russia’s most profitable strategic enterprises – in the oil and gas, energy, nuclear industries, and so on. Until September 2027. Without payment, of course.

Alexei Gorin